The Language of Tibet More Than Just Words

The Language of Tibet More Than Just Words

When you ponder the idea of language in the context of Tibet, a rich tapestry of cultural and spiritual communication emerges, woven tightly through centuries of tradition. Many people might think of Tibetan as simply the language spoken in Lhasa or chanted in Buddhist rituals. But its significance runs deeper, intertwining with every aspect of Tibetan life and art, particularly in the creation of thangkas, those mesmerizing scroll paintings that capture the divine on silk.

Tibetan, as a state language, serves not just as a medium of communication but as a vessel for preserving and continuing the cultural legacy of the region. It’s the language in which ancient texts are written, the dialogue in which timeless stories are shared. Historically, the Tibetan script itself is a marvel, developed in the 7th century — a time when the cultural and spiritual dialogue between Tibet and neighboring regions was flourishing. It reflects not just the phonetics of spoken words but embodies a deep spiritual resonance. Every stroke of the script carries with it the weight of history, much like the careful brushstrokes of a thangka.

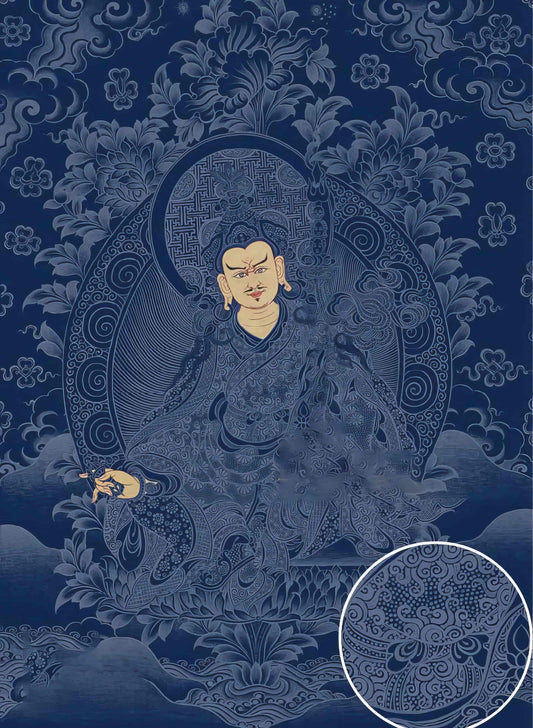

Thangka paintings, often saturated with vibrant natural pigments, speak a language all their own, visually layered with symbolism derived from texts written in Tibetan. Each color and depiction in a thangka isn’t merely aesthetic; it represents particular spiritual aspirations and narratives. The blue skin of a deity, for instance, symbolizes the infinite nature of the sky, a concept captured in both word and image. This duality — word and representation — showcases the symbiotic relationship between the language and the art form.

Craftsmanship in thangkas demands an understanding of the spiritual language. Those who train in the art spend years mastering not only the technical skills of painting but also the spiritual messages conveyed through symbolism and arrangement. The spiritual lineage passed from teacher to student is, in essence, a linguistic transmission — not in the conventional sense of vocabulary or grammar, but in the intangible articulation of faith and philosophy.

One of my fondest memories is watching a thangka artist at work in a bustling studio in Kathmandu. The artist, immersed in concentration, seemed to communicate with the canvas through an unspoken dialogue, each brushstroke as deliberate as a carefully chosen word in a sacred text. Observing this process revealed to me how language transcends the spoken or written form in Tibet — it becomes an experience, a feeling, an understanding.

While modernity might introduce new challenges to preserving the Tibetan language, the cultural threads continue to weave strongly through artforms like thangkas. Whether in a temple, art studio, or in the heart of the Himalayas, Tibetan as a language and a cultural cornerstone remains a testament to the resilience and vibrancy of a rich, living tradition. And just like in thangka art, where every color and pattern tells a story, the language of Tibet remains a narrative, a conversation that continues to evolve.