Chinas Influence in Tibet Threads in the Fabric of Culture

Chinas Influence in Tibet Threads in the Fabric of Culture

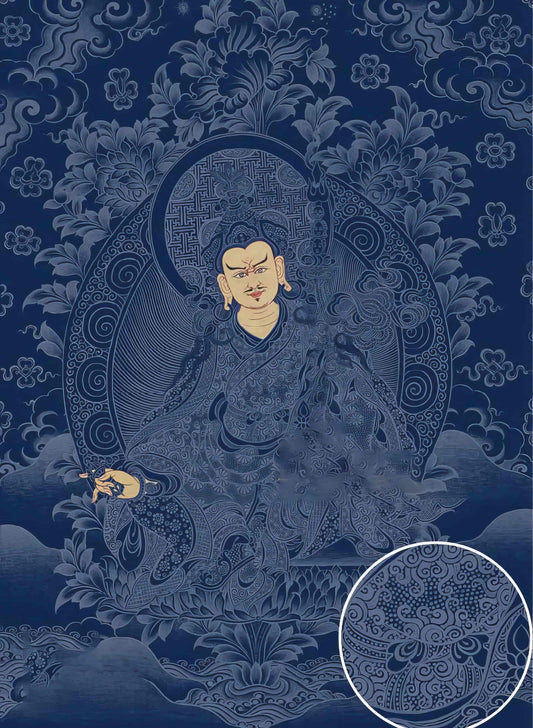

In the heart of Tibetan culture, thangkas — those meticulously crafted, vibrant scroll paintings — have long served as spiritual doorways, inviting viewers to step into a world of profound symbolism and spiritual devotion. Traditionally, these works of art demand both patience and reverence, their creation deeply entwined with the Tibetan identity. Yet, as is often the case in regions of cultural richness and complexity, outside influences ripple through the fabric of tradition. The question of what China is doing in Tibet is not just political, but deeply personal for the artists and spiritual practitioners who call Tibet home.

One angle through which we can examine China's presence in Tibet is its impact on thangka painting itself. The production and sale of thangkas have burgeoned into a substantial industry, with Chinese-run workshops and art schools popping up to meet international demand. In some cases, this has led to a shift toward commercially driven aesthetics, with artists producing works that emphasize visual appeal over spiritual accuracy. The pigments, once painstakingly extracted from natural minerals and plants, are increasingly replaced by synthetic alternatives. The loss here is twofold: it compromises not just the integrity of these sacred paintings, but also the intimate relationship between the artist and the materials, a connection that is as meditative as it is creative.

However, to view this influence solely as detrimental would be to overlook the resilience inherent in Tibetan culture. In response to these changes, many Tibetan artists and spiritual leaders have redoubled their efforts to preserve traditional methods and teachings. There are master thangka painters dedicated to passing on their knowledge to the next generation, ensuring that the authentic spiritual essence of these artworks is not diluted. Workshops still exist where young artists learn the time-honored techniques of grinding stones into the very pigments that breathe life into a thangka, infusing each brushstroke with decades of history and devotion.

This push and pull between commercialism and tradition raises important questions about cultural preservation and adaptation. How does one maintain the sanctity of a spiritual practice while also engaging with the shifting tides of modernity and economic necessity? This is a delicate, ongoing conversation in Tibet, one that continues to weave together the old and the new.

And then there is the matter of cultural expression, which goes far beyond art itself. The Chinese government's policies in Tibet often emphasize assimilation while simultaneously promoting a curated form of cultural heritage — one that's more palatable for tourism and less likely to encourage dissent. Monasteries, once the throbbing heartbeats of Tibetan communities, are now also tourist attractions, sometimes losing their sacred essence in the process. Yet, Tibetan people remain quietly resilient, continuing their spiritual practices, sharing their stories, and teaching their children the values passed down through generations.

In the end, what China is doing in Tibet is complex and multifaceted, marked by a blend of control and modernization. But within the nuances of this relationship, Tibetan culture pulses with a vitality that steals away from easy categorization. Just as the beating heart of a thangka is the devotion it embodies, so too does the heart of Tibet continue to beat — quietly, insistently, defiantly. And isn't that the essence of any enduring culture: the ability to persist, adapt, and hold fast to what truly matters?