Tibets Independence A Tapestry of History and Culture

Tibets Independence A Tapestry of History and Culture

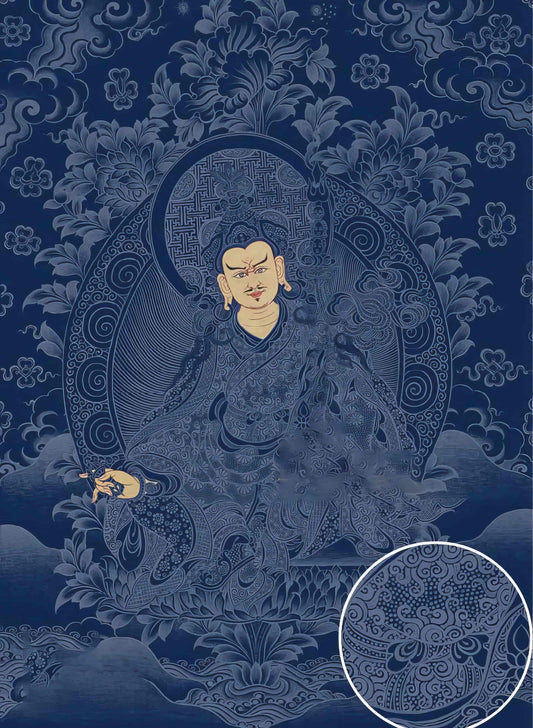

To discuss Tibetan independence is to unravel a tapestry that intertwines threads of political history, cultural vitality, and spiritual richness. This question of when Tibet was independent may initially seem straightforward, but like the intricate patterns of a thangka, its depth is revealed only upon closer examination.

Historically, Tibet has experienced periods of both autonomy and subjugation, each era colored by its own geopolitical landscape. The 7th to 9th centuries saw the rise of the Tibetan Empire, a formidable force under the reign of King Songtsen Gampo. During this golden age, Tibet was a sovereign power, engaging diplomatically with neighboring regions and establishing Buddhism as a foundational element of Tibetan culture. It was also during this time that Tibetans began to cultivate distinct artistic traditions, like thangka painting, which would eventually become a quintessential expression of their cultural and spiritual identity.

Fast forward to the early 20th century, following the collapse of the Qing dynasty, when Tibet experienced a brief period of de facto independence. The 13th Dalai Lama declared Tibet separate from China in 1913, a status maintained until 1951. These years were not merely a political footnote but a significant chapter where Tibetan cultural expressions flourished. The art of creating thangkas, for instance, continued to be a spiritual practice deeply embedded in the fabric of everyday life, connecting the people to their Buddhist beliefs and the larger cosmic order.

In the thangka, one finds a reflection of Tibet's enduring spirit — each piece crafted with painstaking devotion using natural pigments ground from minerals, plants, and even precious stones. One can imagine an artist, seated cross-legged on a cushion, meticulously applying each stroke with a brush made of animal hair, the thangka slowly unfurling like the story of Tibet itself. These paintings are not merely decorative but are meditative tools and conveyors of spiritual teachings, embodying the complexities of impermanence, compassion, and wisdom.

Therefore, any discussion of Tibetan independence cannot be separated from its cultural and spiritual dimensions. The resilience of Tibetan art forms, such as thangka painting, serves as a reminder that culture and spirituality are powerful forces of identity and agency, resilient through centuries of change and challenge.

Beyond historical dates and political boundaries, the question of Tibetan independence is also about the preservation of a rich cultural legacy. It’s about allowing the Tibetan people to continue to tell their stories, paint their thangkas, and pass on their spiritual traditions. As we marvel at the beauty and depth of a thangka, we are invited to reflect on Tibet's unique story — one of resilience, artistry, and an indomitable spirit.