Yaks Looms and the Woven Tapestry of Tibetan Life

Yaks Looms and the Woven Tapestry of Tibetan Life

There’s a moment in the heart of a Tibetan winter, when the world feels edged in white and the air is crisp as the crack of a bell. During these times, the embrace of a yak wool shawl can be as vital as it is comforting. The yak, a creature as emblematic to the Tibetan plateau as the eagle is to the sky, provides more than warmth. It offers a tactile link to the land and its rhythms.

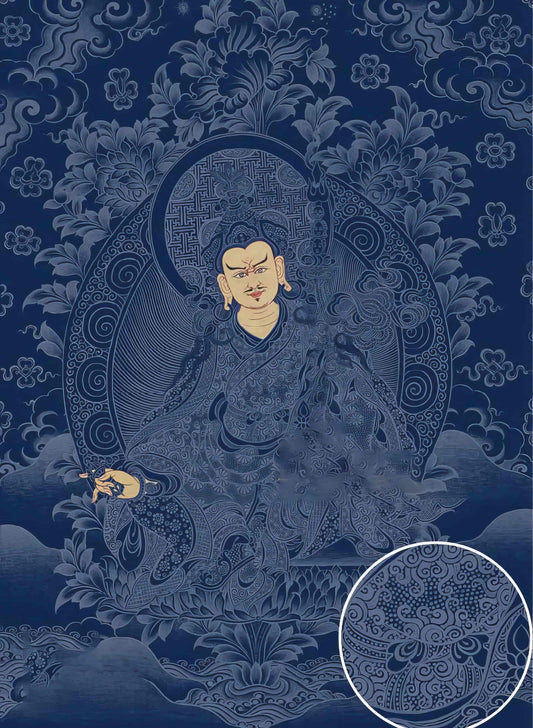

Yak wool, dense and resilient, is more than a mere material; it’s a testament to the harmony between people and their environment. This symbiotic relationship is akin to the connection between a thangka artist and their canvas—a study in patience, dedication, and a profound understanding of natural resources. Just as a painter meticulously grinds minerals into vibrant hues, the wool is processed with care, creating a fabric that tells a story of survival and spirituality entwined.

In Tibetan culture, the shawl is not just an accessory, but a ritual object imbued with meaning. It wraps not only the body but also the spirit, offering protection and connection in one soft sweep. Many pilgrims, during their long journeys to sacred sites, carry a shawl for warmth against high-altitude winds, yet it also serves as a portable altar, a space for meditation or prayer when unfurling before a mountain vista.

The craftsmanship of a yak wool shawl reflects a rich tapestry of traditions. Each thread represents hours of labor, and each pattern, a story passed from generation to generation. The process of weaving is akin to the creation of a thangka—both require an artisan’s practiced hand and an artist’s eye for balance. The colors, drawn from natural dyes, echo the earthy palette of this highland horizon, much like the pigments that bring sacred images to life in thangkas.

Historically, the art of weaving has been a collective endeavor, with entire families and communities participating in the creation of a single shawl. This communal aspect reflects a deeply rooted ethos of interconnectedness, not unlike the monastic workshops where thangkas are born. In both settings, the act of creation becomes a meditation on unity, where the sum is greater than the individual parts.

In contemplating the yak wool shawl, one can’t help but think of the broader fabric of Tibetan life, where every piece has its purpose and story. Whether draped around shoulders or laid upon an altar, the shawl serves as a reminder of the strength found in nature and community—a piece of living history that, even when worn, never loses its warmth.

For those of us far from the Tibetan plateau, wrapping oneself in such a shawl is an invitation to pause and reflect on the threads that weave through our own lives. In exploring the yak wool shawl, we are reminded that warmth is not just a physical state but a gesture of the heart.