Woolly Beast of Tibet

Woolly Beast of Tibet

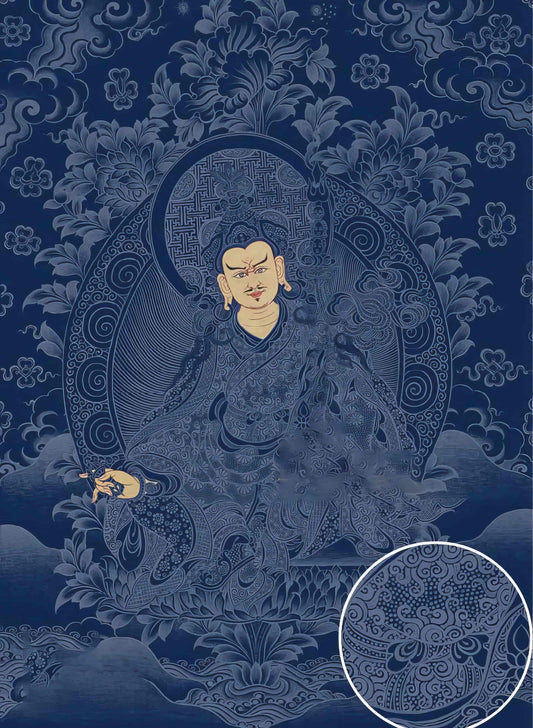

In the heart of the Tibetan plateau, where the land meets the sky and the chill of the wind can pierce even the sturdiest layers of clothing, thrives a creature of both strength and serenity: the yak. Far more than just a beast of burden, the yak is woven into the very fabric of Tibetan life, culture, and spirituality. When I first encountered a thangka painting featuring a yak, its presence was more than material; it evoked the raw yet tranquil beauty of the highlands, a landscape as much internal as it is external.

In thangka art, yaks are not mere depictions of nature's brute force; they embody a divine dance between life and environment. You'll often find these majestic creatures painted amid swirling clouds, flowing rivers, or tranquil meadows, reflecting their role as nurturers, offering sustenance and warmth. Their thick, woolly coats—rendered with meticulous brushstrokes—carry not just pigments but the essence of survival and resilience. Traditionally, thangka artists use natural, locally sourced pigments, grinding minerals and plants into vibrant colors that mirror the earthly tones of the Tibetan landscape. In doing so, they honor the yak’s home with every brushstroke.

But why the yak? To truly understand, one must immerse in the narratives that float around Tibetan hearths. These stories often speak of spirits and deities for whom the yak is a favored companion, a testament to its perceived purity and strength. In Tibetan Buddhism, animals are symbols of various enlightened qualities. The yak, often associated with the Buddha Akshobhya, stands for steadfastness and unyielding dedication. It's a quality that resonates deeply with those who live amid the challenges of altitudes and elements that test both body and mind.

Cultural reflections on the yak go beyond the visual; they permeate daily Tibetan life. A yak's wool, spun into the finest thread, becomes the canvas for earthly and spiritual storytelling in thangka art. Its milk nourishes, its meat sustains, and its very presence inspires a profound sense of gratitude and interconnectedness. You’ll even find their dung—a humble offering—carefully dried and used as fuel, turning necessity into a gentle reminder of ecological stewardship.

One cold morning in a small Tibetan village, a story I heard stayed with me, lingering like the smoke from a butter lamp. An elder spoke of a time when a visitor, unfamiliar with mountainous life, asked why the villagers revered the yak so much. Smiling, the elder simply led the guest to a viewpoint overlooking the grazing herds. "See those yaks?" he said. "They walk paths we could never journey alone."

So, the yak is more than a woolly beast; it is a symbol, a livelihood, a teacher. Much like a carefully rendered thangka, it invites us to explore layers of meaning, encouraging us to look beyond the surface, to ponder the deeper connections that sustain life in places as isolated and profound as the Tibetan plateau. In doing so, it reminds us of the importance of community, balance, and quiet strength—lessons we might all take to heart, wherever we call home.