When Tibet Was Part of India Art Culture and Connection

When Tibet Was Part of India Art Culture and Connection

There’s a wistful curiosity that surrounds the notion of "when Tibet was part of India." It's a question that time and history answer with layers, rather than lines. While Tibet was never politically part of India, the ancient cultural and spiritual ties run deep, and nowhere is this more beautifully illustrated than in the art of thangka.

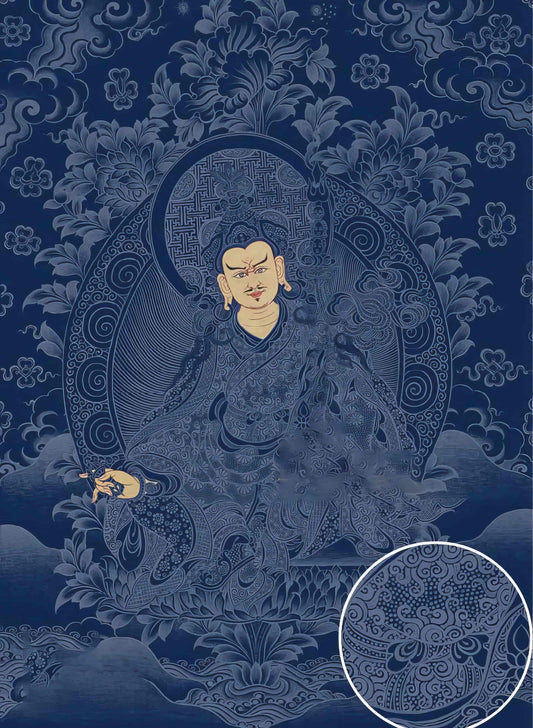

To understand the relationship between Tibet and India, it’s essential to step into the world of Buddhism, a spiritual tradition that India gave to the world over 2,500 years ago. As Buddhism traveled north to Tibet, it carried with it not only the teachings of the Buddha but also a vivid visual storytelling form: thangka paintings. These intricate works of art are more than decorative; they are spiritual maps guiding practitioners on their meditative journeys.

A thangka is more than the sum of its pigments and silk borders. The process of creating a thangka involves discipline akin to a spiritual practice. Every stroke, every hue is imbued with meaning, crafted by artists who undergo years of rigorous training. This artistry reflects a confluence of Indian iconography and Tibetan interpretation. Take, for instance, the use of natural pigments derived from minerals and plants — a practice rooted in Indian tradition and adapted to the Tibetan landscape. The vibrant palette of a thangka is both a nod to and a divergence from its Indian roots, reflecting the unique environmental and cultural narratives of the Tibetan plateau.

The journey of thangkas from Indian Buddhist monasteries to the heart of Tibetan spiritual life is a testament to the borderless nature of cultural transmission. Think of the revered figure of Avalokiteshvara, the embodiment of compassion. Originating from Indian scriptures, this bodhisattva has been lovingly depicted in countless thangkas. Yet, over time, the imagery evolved, absorbing Tibetan influences to create a figure that is both familiar and distinct. In its Tibetan form, Avalokiteshvara’s eleven heads and a thousand arms are illustrated with a delicacy that speaks to the intricate dance between tradition and innovation.

This cultural exchange was not solely in the realm of the sacred. The art of thangka-making itself became a confluence of Indian rigor and Tibetan spirituality. Indian artists brought the foundational techniques, while Tibetan monks and artisans imbued each piece with a unique spiritual significance. The thangka became a canvas where Indian artistic discipline met Tibetan spiritual fervor, a fusion that continues to inspire admiration.

While the geopolitical narratives might speak volumes about borders and sovereignty, the cultural story tells of shared heritage. The threads connecting Tibet and India are woven into the very fabric of thangka art, reminding us that borders cannot confine the flow of culture and spirituality.

It’s this rich intermingling that makes exploring the history of thangkas feel like tracing the steps of an age-old dance — one that invites us to reflect on how deeply interconnected our world has always been. In unraveling the threads of the past, we discover not only the beauty of these artworks but the enduring connections that transcend time and territory.

And so, when we ponder the question of Tibet and India’s historical relationship, perhaps the answer lies not in territorial maps but in the vibrant colors and spiritual stories of a thangka, where history and art lovingly embrace.