When Tibet Merged With China A Cultural Reawakening Through Thangka Art

When Tibet Merged With China A Cultural Reawakening Through Thangka Art

The year 1950 marked a seismic shift for Tibet when the People's Liberation Army of China entered its territory, initiating a complex and often painful integration process. The political narrative during this period is one of strife and change, yet if we look beneath the surface, particularly through the lens of Tibetan thangka art, we uncover a story of cultural resilience and transformation.

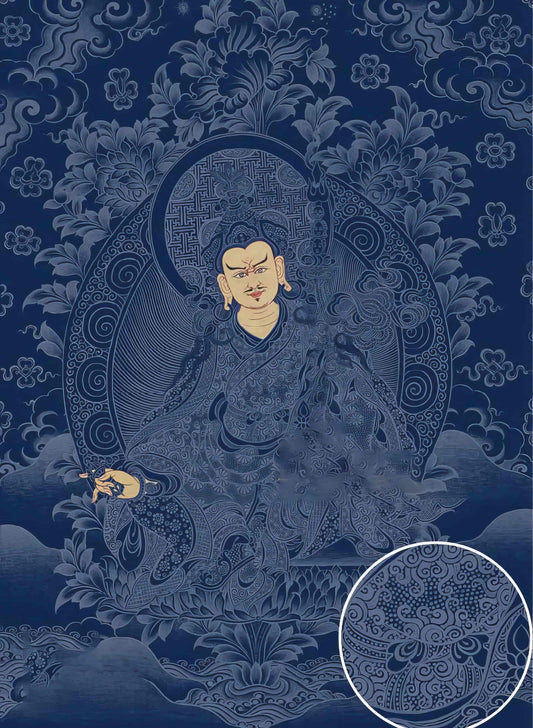

The thangka, with its vibrant depictions of deities, mandalas, and spiritual narratives, has long been a cornerstone of Tibetan Buddhism. These scroll paintings — intricate, purposeful, and often breathtaking — serve not only as teaching tools but also as meditative aids and devotional artifacts. The pigments, mixed painstakingly from minerals and plants, vary with each lineage and regional style, each hue imbued with spiritual significance. This is where the story gets truly interesting. Even as political pressures mounted, the art of thangka painting experienced a subtle but telling evolution.

During the years following 1950, the traditional transmission of thangka art faced unprecedented challenges. Many master painters found their teachings interrupted, monastic institutions disbanded, and the sacred art was at risk of losing its lineage. Yet, in the way of all meaningful cultural practices, it adapted, sometimes quietly, sometimes with astonishing flair. Hidden within private homes, passed down with whisperings of lineage stories, and even shared in exile communities, the essence of thangka art found new pathways.

One significant shift observed in this period was the emergence of hybrid styles — a blending of ancient Tibetan techniques with new Chinese influences. Some artists began to incorporate Chinese motifs and styles into their thangkas, expanding the visual and symbolic vocabulary of the art. This was both a necessity and a reflection of a new shared cultural tapestry. Yes, there was loss, but there was also a newfound expression that acknowledged a complex cultural identity.

Moreover, the dedication to using traditional methods — from grinding mineral pigments by hand to maintaining the spiritual discipline required to paint a deity’s form — persisted. Painting a thangka is not merely an artistic endeavor; it is a spiritual discipline, a form of meditation that demands the artist's complete immersion in the symbolism of each line and color. It is said that the painter's own spiritual development is woven into each brushstroke. This devotion has ensured that, despite the political and social upheavals, the heart of thangka painting continues to beat with vitality.

In examining this period through thangka art, we find a nuanced narrative that goes beyond the headlines. The merging of Tibet with China was indeed a crucible, but within it, Tibetan culture found ways to endure and, at times, flourish. Whether in a depiction of the Medicine Buddha or the ethereal landscapes of a mandala, thangka paintings offer us living proof that cultural identity, like art itself, is resilient and ever-evolving.

And while the canvas has expanded, the threads of tradition remain tightly woven. When we look into a thangka today, we don't just see a static piece of art; we see the echoes of a people who have adapted, survived, and continue to tell their stories with grace and dignity. It's a reminder that even amidst cultural and political shifts, art remains a steadfast vessel of heritage and hope.