Tibetan Thangka vs Nepali Paubha A Tale of Two Traditions

Tibetan Thangka vs Nepali Paubha A Tale of Two Traditions

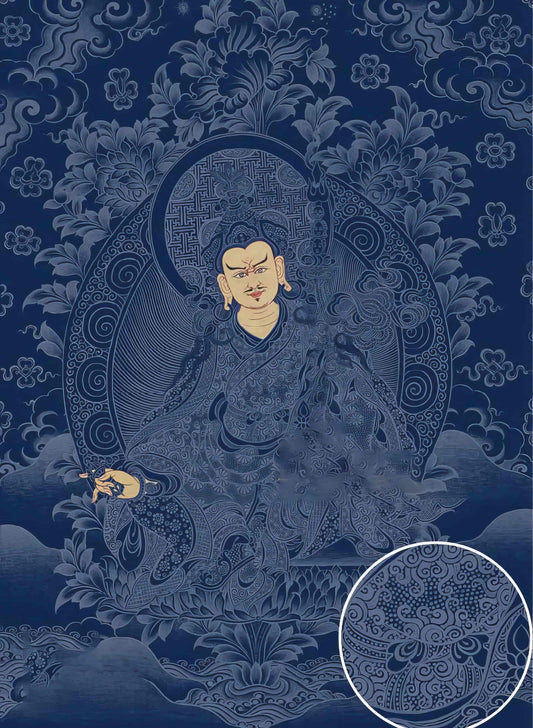

When walking into a serene monastery in the Himalayas, one's gaze might be captured by a vibrant thangka hanging on a wall, its intricate patterns narrating a timeless spiritual story. A few valleys over, amidst the bustling streets of Kathmandu, you might encounter a similar visual allure, but the painting is a Nepali paubha. Despite their shared Buddhist roots and geographical proximity, these two art forms diverge in their techniques, styles, and cultural contexts.

Thangka painting in Tibet is a deeply spiritual form of art. It starts with the canvas stretched and mounted on a wooden frame, coated with a mixture of yak hide glue and chalk. This meticulous preparation is symbolic, laying the foundation for the spiritual journey depicted in the artwork. The pigments are derived from natural minerals: lapis lazuli, malachite, and cinnabar, among others, each chosen for their spiritual significance and luminous qualities. The rigorous training of a thangka artist is akin to a spiritual practice itself, demanding years of study under the guidance of a master, honing the ability to imbue each brushstroke with devotion.

Contrast this with the Nepali paubha, which also cherishes natural pigments, but often introduces gold and silver foils to create resplendent contrasts that play with light. The technique has been refined over centuries by Newar artists, whose cultural intersections with Tibetan Buddhism and Hinduism provide a unique narrative flair. The contours in a paubha often suggest a sensuous fluidity, a Newar touch that breathes life into each deity's form.

Both thangka and paubha paintings serve meditative purposes, yet they reflect the distinct spiritual landscapes from which they arise. Thangkas act as visual aids in meditation, often featuring mandalas or specific deities to facilitate spiritual exercises. They are portable, designed to be rolled up and carried by monks traveling across the vast mountainous terrains of Tibet. In Nepal, paubhas typically hold a more permanent place within temples or homes, where they are revered as both art and sacred relics.

Even their representations of shared Buddhist deities highlight this divergence. A Tibetan Avalokiteshvara might emphasize serene compassion, with a symmetrical, almost architectural portrayal, guiding the viewer into contemplation. Meanwhile, a Nepali rendition would capture the god's dynamic vitality, each detail a testament to the artist's devotion.

As I reflect on the cross-cultural tapestry woven by these two traditions, I am reminded of the profound diversity within the seemingly monolithic term "Buddhist art." Each painting, whether a Tibetan thangka or a Nepali paubha, is a testament to a community’s spiritual and aesthetic ideals. Despite their differences, both stand as vibrant guardians of cultural heritage and spiritual insight. Next time you encounter one of these paintings, perhaps pause a little longer, see the story it tells not just of a deity, but of an entire tradition. Every line and color is a dialogue, centuries in the making, between the artist, culture, and viewer.