Zenith Tibet Almond Stick and the Hidden Art of Thangka Restoration

Zenith Tibet Almond Stick and the Hidden Art of Thangka Restoration

In the vibrant world of Tibetan thangka art, every brushstroke carries layers of meaning and history. What many admirers often overlook is the care these scroll paintings require once they leave the artist's hands. Much like the monks who meticulously craft them, thangkas demand respect and nurturing, revealing an unexpected connection to an unusual tool: the Zenith Tibet Almond Stick scratch remover.

For those unfamiliar, the almond stick is a cherished item among artisans and collectors alike, particularly loved for its ability to imbue life back into scratched or faded wood surfaces. It might seem odd to discuss this tool in the context of thangkas—a medium of pigments and cloth rather than wood—but therein lies one of the many tangents that art restoration can take. The stick’s utility is not limited to wood; it exemplifies the art of mindful restoration, echoing the patience and dedication inherent in thangka painting itself.

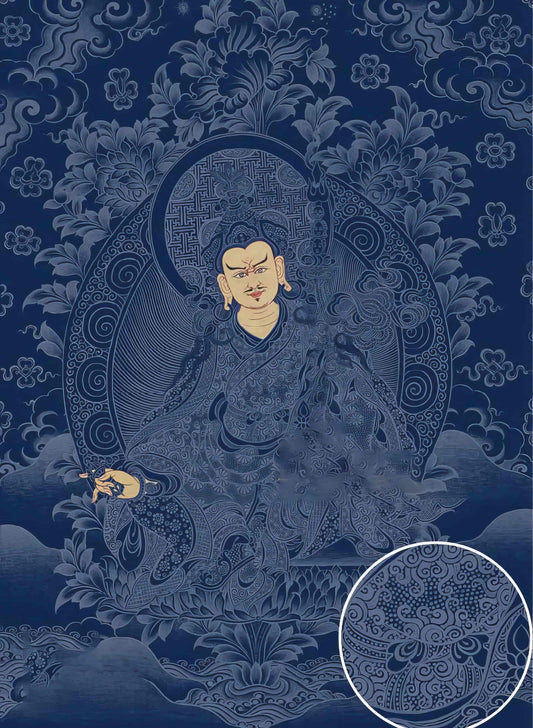

Thangkas are more than just beautiful depictions of divinities or mandalas. They embody the spiritual teachings of Buddhism, with each detail meticulously rendered to convey profound truths. Artisans undergo years of rigorous training, learning not only the craft but the spiritual narratives behind each depiction. The pigments, too, are often derived from natural materials, such as saffron or lapis lazuli, each chosen for its symbolic resonance and historical significance. Restoration, therefore, must honor this complexity and respect the original intent of the creator.

In this sense, the gentle touch required in removing blemishes or signs of aging from a thangka parallels the application of the almond stick. Both processes are acts of reverence—recognizing the value of timeworn beauty while careful not to erase its history. To a thangka lover, there’s a certain satisfaction in knowing that the essence of the piece remains intact, akin to the spiritual integrity maintained in an ancient monastery.

Reflecting on my own experiences, this practice of delicate restoration calls to mind the quiet mornings spent in Tibetan workshops, where artists sit cross-legged, losing themselves in the rhythmic precision of their craft. It’s a place where art exists in dialogue with meditation, and where the significance of each line drawn goes beyond the visual, establishing a living connection between past and present.

As we consider the ever-evolving journey of a thangka—its creation, its aging, and its subsequent care—there is something profound in realizing that even something as humble as an almond stick can have a role in preserving this sacred art form. The tool itself becomes part of the narrative, a testament to cultural continuity in an ever-changing world.

In this way, perhaps we can see the almond stick not just as a scratch remover, but as a symbol of the enduring relationship between art, history, and the human touch—a reminder that even the smallest acts of restoration can carry a weight of significance.