Yaks and Their Profound Presence in Tibetan Culture

Yaks and Their Profound Presence in Tibetan Culture

In the windswept landscapes of Tibet, the yak is more than just an animal. It’s a lifeline, a symbol, and, quite artistically, a muse. Often, the first sight of these rugged creatures against the backdrop of a vast, rolling plateau draws a deep breath of reverence from travelers. But their role transcends the mundane; yaks are steeped in the spiritual and cultural fabric of Tibetan life, and their influence even extends into the realm of Tibetan art, particularly thangka paintings.

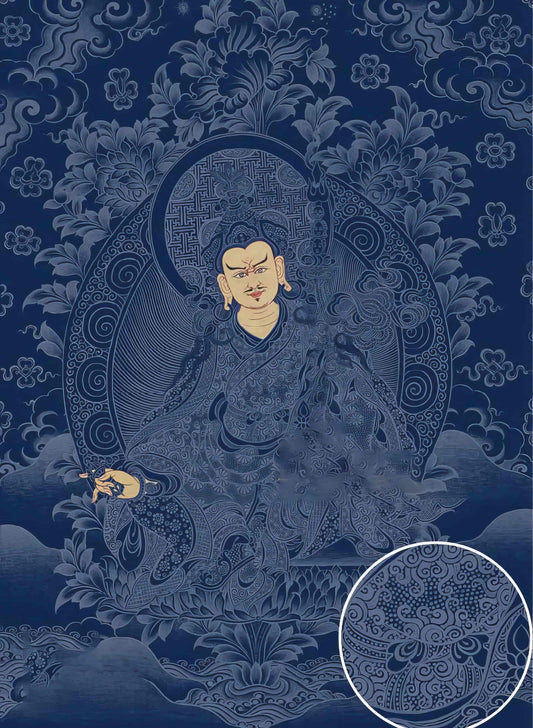

Thangkas, those rich tapestries of spiritual narrative and intricate symbolism, occasionally pay homage to the yak. Not merely for the creature’s physical utility but for its emblematic resilience. The yak, with its unyielding spirit, mirrors the human journey through the wild terrains of both nature and soul. When a thangka artist chooses to incorporate a yak, it’s not a mere nod to pastoral life; it’s a profound statement on the capacity for endurance and grace under pressure.

The artistry involved in depicting a yak in a thangka is no small feat. Traditional thangka artists, often trained over many painstaking years, adhere to strict guidelines to maintain the spiritual integrity of their work. These paintings are more than decorative; they are meditative tools, steeped in symbolism and precise iconography handed down through generations. Natural pigments derived from elements like crushed stones and plants provide the thangka’s palette, creating a harmonious connection to the very landscapes where yaks roam. The laborious process of preparing these pigments can take weeks, sometimes months, reminding us of the balance found in nature’s patience and chemistry.

In Tibetan mythology, the yak sometimes appears as a symbol of strength and steadfastness. It is not uncommon to hear tales of yak caravans traversing treacherous mountain passes, their burdens heavy with salt or barley, but their spirits unbroken. This historical significance enriches the yak’s representation in art, where it becomes a metaphor not just of physical perseverance but of spiritual journeying as well.

Interestingly, yaks are also tied to the cultural practices of Tibetan society. They provide wool for traditional garments, milk for sustenance, and even dung for fuel—a testament to their integral role in daily life. Such connections underline why the yak is revered, not just as a beast of burden but as an entity deserving of respect and gratitude. In this regard, the yak becomes a living teaching of interconnectedness, a theme beloved in Buddhist philosophy.

When we see a yak depicted in a thangka, whether it stands alone or accompanies deities like Padmasambhava, it invites the viewer to contemplate their own inner strength. Are we not all, in our ways, navigating the high passes of our personal landscapes? The yak, both common and mystical, becomes an invitation to reflect on our grounding principles and the sacred textures of our journeys.

So the next time you encounter a thangka, take a moment to look beyond the immediate intricacies. You might find a gentle, enduring spirit hidden in the swirls of color and detail—a silent witness to the resilience found within us all.