Which State of Being is Your Thangka Painting

Which State of Being is Your Thangka Painting

Flipping through the colorful pages of a book in a tiny library in Lhasa some years ago, I stumbled upon a phrase that has stayed with me: "Thangka is not just art; it's a mirror." The deeper I delve into the world of thangka, the more I understand the layers behind this simple yet profound statement. Thangkas are indeed mirrors—reflective in nature, capturing the vastness of Tibetan spiritual landscapes, and presenting them in all their colorful, meditative glory.

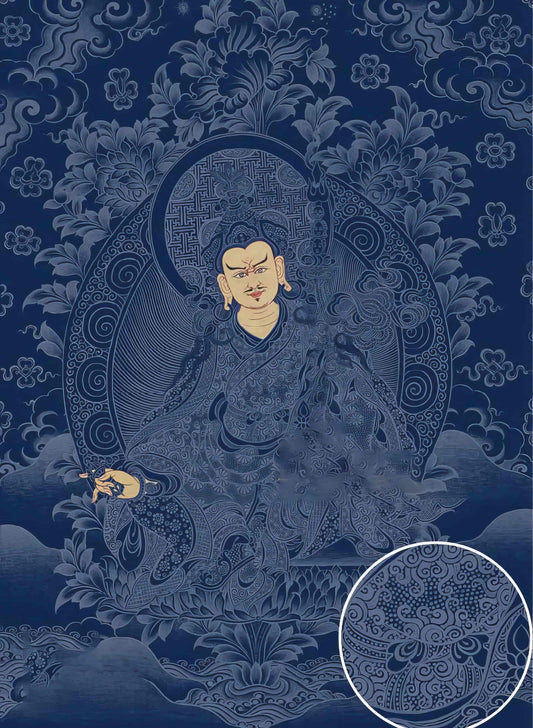

Perhaps you've stood before a thangka and felt the pull of its vibrant hues, the intricacy of its designs. Indeed, one of the most engaging aspects of thangka painting is its use of natural pigments—crushed minerals like malachite for green, lapis lazuli for blue, and pure gold to highlight sacred figures. These pigments do more than catch the eye—they carry the weight of centuries and symbolize the transition of earthly materials into spiritual narrative. This transformation mirrors the Buddhist journey, where the temporal evolves into the enlightened.

Symbolism is key in thangka paintings, and each element carries significance—like the wheel (Dharmachakra) signifying the teachings of Buddha, or the lotus, a representation of purity and spiritual awakening. Intricately detailed, these symbols are meticulously hand-painted through a meticulous process that fascinates onlookers and artists alike. It's not just a technical skill but a discipline that demands years of rigorous training. Each stroke becomes an act of meditation, where the painter is in a state of mindfulness, channeling both tradition and spiritual intent onto the canvas.

But thangka is not monolithic; it reflects the diverse tapestry of Tibetan culture. Regional styles vary, each infusing distinct artistic tendencies and spiritual interpretations woven into the fabric of its lineage. In the Ngari region, thangkas are known for their subtle shades and refined lines, whereas the eastern Himalayan region of Amdo yields thangkas rich in vibrant, bold strokes that reflect the rugged, sweeping landscapes. This variety prompts an intriguing reflection: just as the thangka artists adapt their craft to suit local aesthetics and spiritual subtleties, we are invited to find the thangka that resonates with our personal state of being.

Reflecting on this, I often ask myself—and invite you to ponder—what state of being your thangka reflects. Is it one of serene compassion embodied in Avalokiteshvara? Perhaps the transformative energy of wrathful deities calls out to those navigating personal challenges. Maybe it mirrors the wisdom of Manjushri, guiding you through a phase of learning and exploration.

So, the next time you find yourself in a gallery or monastery, standing in front of a thangka, take a moment to consider what it reflects back to you. It might reveal more than you anticipated—even holding up a mirror to the subtleties of your own journey. And in that quiet conversation between you and the painting, you might find a moment of stillness, a whisper of timeless wisdom.