When Was Tibet a Country A Journey Through History and Art

When Was Tibet a Country A Journey Through History and Art

Once upon a time, Tibet stood as a kingdom, shrouded beneath the majestic peaks of the Himalayas, a realm where spirituality and sovereignty intertwined. The question of when Tibet was considered a country is neither simple nor singular, wrapped in layers of history and culture that continue to whisper through the centuries. Painting a picture of this is much like crafting a thangka, where every stroke carries meaning and every hue, a story.

Historically speaking, Tibet’s tale as a sovereign entity is most vividly unfurled during the reign of the Tibetan Empire from the 7th to the 9th centuries. This era blossomed under the reign of Songtsen Gampo, who, through alliances and conquests, expanded the kingdom’s reach across significant parts of Central Asia. It was during this golden age that Buddhism took root in the region, brought by the king’s marriage alliances with Nepal and China, leaving an indelible mark on Tibetan identity. Yet, history is a dance of time, and the empire eventually fractured, leading to periods of fragmentation and foreign influence.

The 20th century marked Tibet’s contentious presence on the global stage. For brief periods, particularly after the fall of the Qing Dynasty in China, Tibet exercised de facto independence, culminating in its declaration of independence in 1913. However, geopolitical intricacies and the inexhaustible tide of history led to Tibet’s incorporation into the People's Republic of China in the 1950s, a subject of ongoing debate and sentiment among Tibetans and their supporters worldwide.

As an aficionado of thangka art, I find that Tibetan culture’s endurance and richness offer a poignant lens through which to view these historical shifts. Thangkas, which are far more than mere paintings, encapsulate a microcosm of Tibetan spirituality and artistic excellence. The rigorous training of thangka artists, who often dedicate years to mastering their craft, reflects a deep devotion similar to the spiritual resilience of the Tibetan people. The use of natural pigments — derived from minerals and plants — mirrors the harmonious relationship Tibetans share with their environment, a bond that has remained steadfast even as political borders shifted.

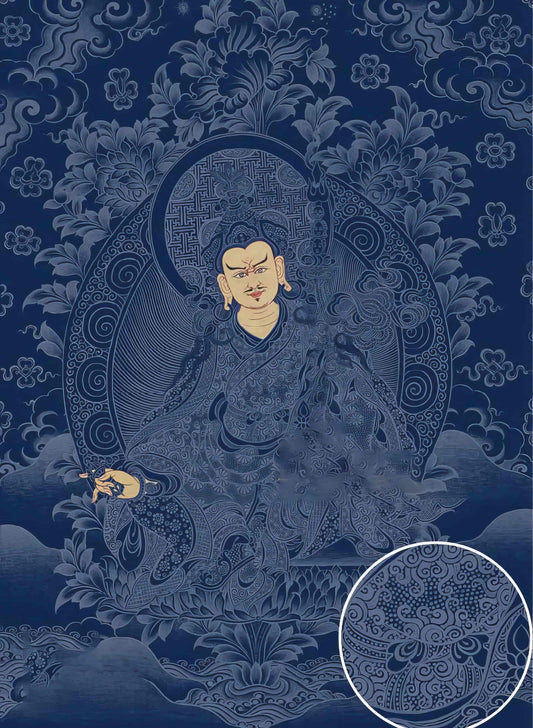

The symbolism within thangkas often conveys narratives of divine protection and wisdom. One finds deities like Avalokiteshvara or Green Tara, whose visages exude serenity and compassion, serving not only as spiritual guides but also as emblematic of a broader cultural continuity. Each intricate detail, whether a scroll’s winding clouds or the delicate foliage surrounding a deity, tells a story of survival and faith, much like Tibet itself.

To view Tibet solely through the prism of its political history would be to miss the rich tapestry of culture and spirituality that defines it. Tibetan Buddhism and its artistic expressions offer a window into a realm where country and culture are inseparable, perpetually entwined like the strands of a well-woven thangka.

As I reflect on Tibet’s status across history, I find myself drawn to the enduring spirit of its people, akin to the timeless application of gold leaf on a thangka, which catches the light irrespective of the shadows around it. In those glimmers, still vibrant and persistent, Tibet endures as a nation of its people, their art, and their spirit.