What Tibetan Monks Eat Nourishment Beyond the Plate

What Tibetan Monks Eat Nourishment Beyond the Plate

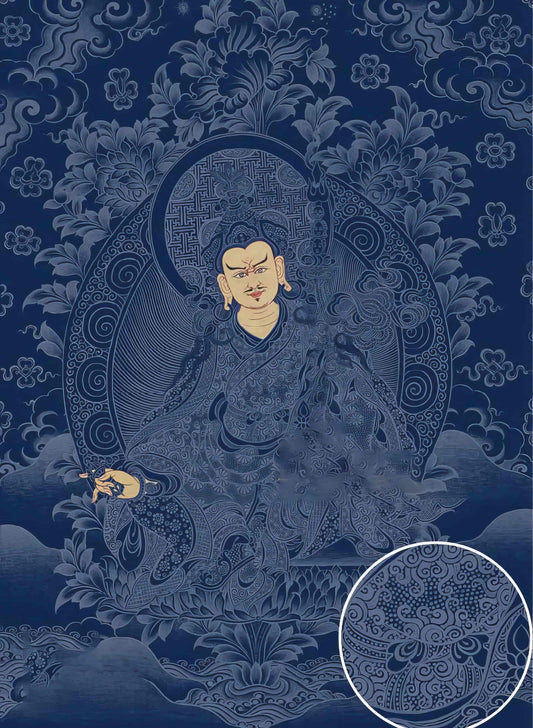

Tibetan monks' meals are less a matter of mere sustenance and more a reflection of their spiritual path, culture, and the unique environment from which they hail. Nestled amidst the high-altitude expanses of the Himalayas, monasteries have long nurtured a relationship between nourishment and spirituality that transcends the typical Western dining experience. I marvel at this approach every time I delve into their world — much like when I lose myself in the intricate details of a thangka painting.

Imagine sitting down to a meal that hums with the same vibration as a carefully unfurled thangka, its pigments made painstakingly by hand from crushed minerals and herbs. The monks' diet is similarly of the earth. Staples like tsampa, a roasted barley flour, become a versatile base, kneaded into dough or stirred into tea. This hearty grain is deeply symbolic, signifying not just physical sustenance but also a profound connection to the land, much like the natural pigments used in thangkas that echo the palette of the Tibetan landscape.

In Tibetan Buddhism, food is entwined with mindfulness and gratitude. Each meal is an opportunity to practice compassion. You might observe monks eating a simple bowl of thukpa, a noodle soup, with a palpable sense of reverence. It's not unlike the care a thangka artist takes in choosing the precise shade and brushstroke to manifest a deity's serene expression. The art of consuming food, much like the creation of a thangka, is an active practice of presence, an art in itself.

Culturally and historically, the Tibetan diet has been shaped by its harsh terrain. Dairy is prominent, with yak butter both a culinary staple and a cultural keystone. If you pass through a monastery during Losar, the Tibetan New Year, you'd find a celebration akin to a thangka's vibrant composition, where friends and families share offerings like sweetened rice and freshly brewed butter tea. These dishes weave tales of survival, community, and celebration, reminiscent of the stories each brushstroke in a thangka tells.

While Western sensibilities might prize variety and novelty, Tibetan monastic meals are more about simplicity and continuity. In this way, meals become meditative practices, akin to the hours spent by artists patiently layering the colors of green Tara or wrathful Mahakala. The spiritual value imbued in their meals reminds me of the respect given to each thangka — both are reminders of a lineage that sees beyond the physical, into a field of sacred nourishment.

Perhaps, after all, what Tibetan monks eat is not so much about the ingredients themselves but the spirit with which they're consumed. Meals and thangkas alike invite us to look deeper, beyond the surface, into a world where every grain, every color, and every taste has its place in a grand, interconnected tapestry. Eating, like painting, becomes an act of devotion — a gentle reminder that nourishment is as much about the heart as it is the body.