Visioning Tibet

Visioning Tibet

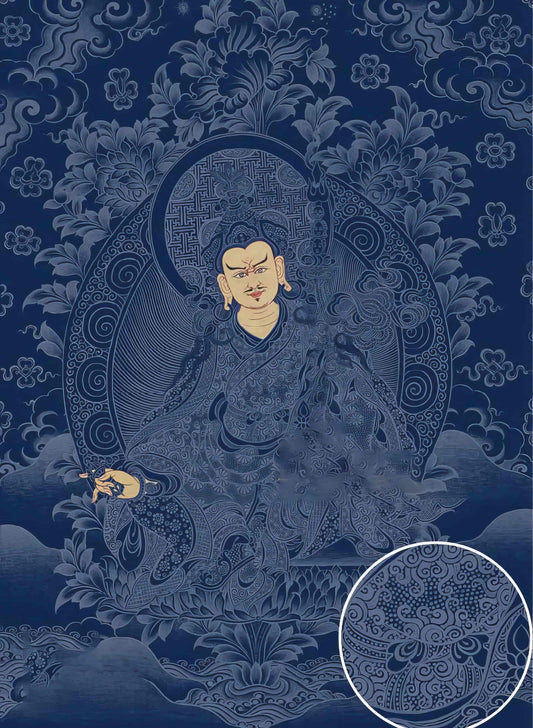

The first time I encountered a thangka, it was not in a crowded marketplace or a museum, but tucked into a quiet chapel of a Tibetan monastery. There, hanging on a wall bathed in soft, yellow light, a painting of Padmasambhava glowed with vibrant hues. This image of the revered Buddhist master sat within a framework of rich blues and fiery reds that seemed to pulse with life. It was a perfect encapsulation of what it means to envision Tibet — a blend of artistry and spirituality, tradition and vision, all woven into a single tapestry.

Thangkas are windows into the Tibetan soul, each stroke of color and detail carrying centuries of history and devotion. The pigments used in these paintings are derived from natural resources: lapis lazuli for blues, cinnabar for reds, and gold dust for accents of divine light. This choice of materials is not simply about aesthetics or availability; it's about linking the earthly to the divine. There's something compelling about these pigments — earthy and mineral-based — that connects each piece to the Tibetan landscape, from the towering Himalayas to the plains of Lhasa.

The training of a thangka painter is as rigorous as the creation process is meticulous. Artists often apprentice from a young age under the watchful eyes of masters, learning not only the technical skills but also the spiritual implications of the work. Each brushstroke is a meditation, each line a pathway to enlightenment. The tradition demands precision, not just in art but in intention. A misplaced dot can disrupt the flow of energy, a poorly drawn deity can alter the spiritual charge of a piece. This is not just painting; it's a prayer captured in color and form.

There's a deep generosity in the way these artists share their creations. While thangkas often serve as teaching tools — visual guides to the complex web of Buddhist philosophies — they also invite personal reflection. As I stood in front of that first thangka, I found myself drawn into its story, contemplating not just the life of Padmasambhava but my own place in a larger spiritual journey. It was as though the painting had extended an invitation to look beyond the confines of the material world and consider the threads that weave us all together.

Reflecting on the cultural variations within Tibet itself, one sees a diverse tapestry of local influences. While the overarching themes in thangkas remain consistent — the representation of deities, the cyclical nature of life — regional styles introduce unique elements. In Amdo, with its sweeping grasslands, you might find thangkas that are more narrative in nature, stories depicted in a continuous line across the canvas. In contrast, thangkas from Lhasa may contain intricate mandalas, complex in their geometric perfection, inviting viewers to traverse the inner landscapes of their own consciousness.

The art of envisioning Tibet through thangkas is about more than just seeing; it's about understanding, connecting, and reflecting. Each piece is a dialog between artist and audience, past and present, self and universe. It is a reminder that, while we may be many miles and cultures apart, there is a shared search for meaning and peace that binds us.

And if ever you find yourself standing before a thangka, take a moment to pause. Let yourself be drawn into the landscape beyond the pigments. In that quiet space, you may just catch a glimpse of Tibet's profound depth and see, if only briefly, the world through its eyes.