Tsampa The Quiet Heart of Tibetan Life

Tsampa The Quiet Heart of Tibetan Life

In the Tibetan Plateau's rugged landscape, where the earth seems to touch the sky, there's a quiet staple that sustains both body and spirit: tsampa. This humble mix of roasted barley flour and butter tea is far more than a meal—it's a touchstone of culture, a steadying weight in the palm of one's hand amidst the windswept vastness. To understand Tibet, one must understand tsampa.

Tsampa's heart lies in its process. Barley, the only grain hardy enough to endure Tibet's harsh climate, is roasted and ground into a fine powder. This process of roasting is akin to a ritual, where time and temperature are the guardians of flavor. The result is a flour that's both nutty and subtle, well-suited to the tradition of simple, soulful sustenance. It's mixed with butter tea, a brew suffused with the warmth of yak butter and the slightly astringent bite of salt, and can be shaped into balls or kneaded like dough. There’s a quiet artistry in this mixing, a moment that feels both grounding and meditative.

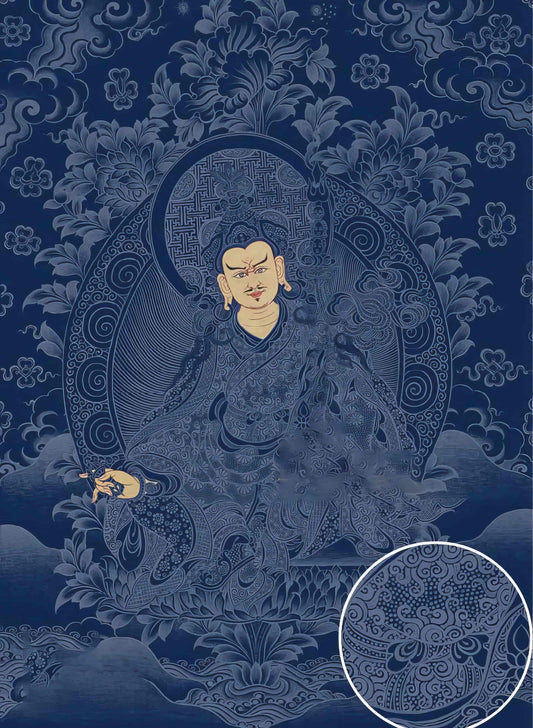

This dish’s place in Tibetan life is woven into the fabric of daily routines and sacred rituals. Tsampa is both the traveler’s food and the monk's sustenance. It’s portable, filling, and nourishing in the way that only something born from centuries of adaptive knowledge can be. In monasteries, young monks might start their day with tsampa, providing the energy needed for hours of meditation or the intricate, steady brushstrokes of thangka painting.

Speaking of thangka, there’s a profound connection between this artistic tradition and the presence of tsampa. Just as tsampa requires careful preparation and the right touch, thangka painting demands years of practice and reverence. Natural pigments, created from ground minerals and plants, echo the earthy tones of roasted barley, each stroke meticulously applied to create elaborate depictions of deities and mandalas. The spiritual intent behind these paintings parallels the mindful preparation of tsampa—both are offerings, both are expressions of devotion.

Historically, tsampa has been a food of resilience and connection. It has fueled caravans across the Silk Road and nourished communities through centuries of isolation and change. In Tibetan gatherings, sharing tsampa is sharing history; it is a gesture of hospitality and an invitation to partake in a collective memory. It’s no coincidence that tsampa is often associated with Losar, the Tibetan New Year, when families come together to celebrate continuity and new beginnings.

For those of us captivated by Tibetan culture from afar, preparing tsampa can be a small but significant act of cultural appreciation. It invites questions and contemplation: How many hands have shaped this same mixture? How many shared conversations and stories does each handful contain?

Ultimately, the beauty of tsampa lies in its simplicity and its capacity to hold so much within so little. It’s a reminder that even in the vastness of Tibetan landscapes—or within the complexity of its amazing thangka paintings—the most profound connections often start with the simplest things.

And maybe that's a lesson for all of us, wherever we find ourselves in this wide world. Tsampa whispers of the power in the familiar, in the things passed hand to hand, heart to heart.