Tibetan Gods and Goddesses Beyond the Canvas

Tibetan Gods and Goddesses Beyond the Canvas

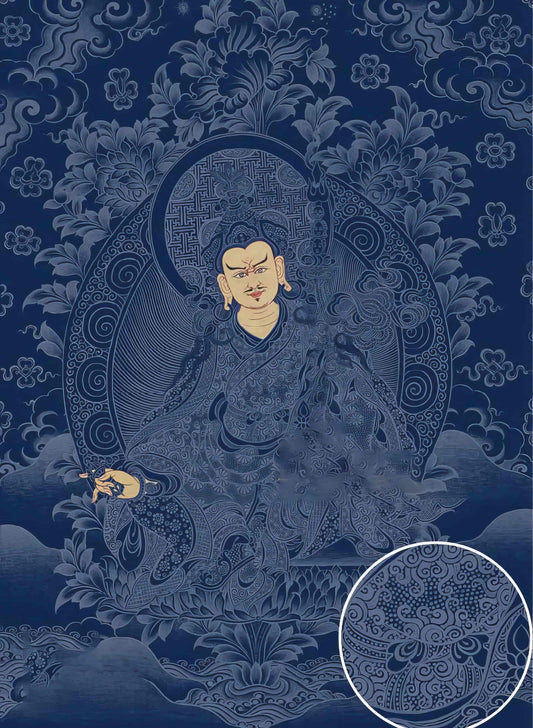

When I first laid my eyes on a thangka, it wasn't the moonlit blues or sunbeam golds that stirred me. It was the staggering presence of the deities themselves — Avalokiteshvara, Tara, and fierce Yamantaka — their faces somehow intent and serene amid the vibrant chaos. Each thangka is a theater of Tibetan spirituality, where gods and goddesses play out their symbolic roles on silk canvases.

Let's talk about Tara, the beloved goddess of compassion and action. Many thangkas depict her in vibrant green, a symbol of life and rejuvenation. Her image is more than an object of reverence; it's an entrance into a narrative of enlightenment and protection. Tara is said to have manifested from the tears of Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, when he wept for the world's suffering. In a rich thangka, you might find her with one leg stepping forward, ready to intervene in the mortal world — a dynamic pose that underscores her active compassion. Painting her isn't just about color and form; it's about understanding the story that breathes life into every stroke.

Now consider Yamantaka, the formidable conqueror of death, often rendered in terrifying shades of reds and blacks, a fearsome counterbalance to Tara's gentleness. In the hands of a master artist, his fierce countenance bursts from the canvas, a powerful reminder of impermanence and the necessity of overcoming inner demons. The paradox is striking: here is a deity who appears monstrous, yet he embodies the ultimate peace that comes from conquering fear. This deeply intricate symbolism requires an artist not just skilled in technique and materials, but deeply immersed in the spiritual teachings that Yamantaka represents.

Creating a thangka is no ordinary artistic endeavor; it’s a spiritual practice that demands rigor and fidelity to a lineage of both technique and vision. Traditional pigments are elemental, derived from minerals and plants — a grounded connection to the earth that complements the sacred motifs being brought to life. Each brushstroke is a meditation, a prayer in itself, demanding a level of patience and devotion that modernity often overlooks.

For the artists, the process is as significant as the final piece. Historical records detail how revered thangka painters undergo extensive training, often under the guidance of masters for years, not just to learn the brush techniques but to absorb the spiritual ethos that underpins the art. It's an inheritance of tradition, passed from heart to hand, preserving a legacy that remains vividly alive.

What strikes me most is how these deities, through such detailed artistry and devotion, become more than religious icons; they become intimate teachers, silent guides in the quest for understanding one's inner landscape. Each god and goddess tells a story, not just with myth but through the delicate interplay of pigment and spirit, canvas and consciousness.

In a world that often rushes past such subtleties, these thangkas invite us to pause, to see beyond the aesthetics, and to contemplate the narratives woven into every intricate line. It's a reminder that true art — the kind that evokes, challenges, and inspires — is as much about the journey as the destination. I suppose that's the real allure of these Tibetan gods and goddesses: they call us back to something profoundly human.