Tibetan Culture and Thangka Art in the Shadow of 1950

Tibetan Culture and Thangka Art in the Shadow of 1950

To understand the fragile endurance of Tibetan culture and the intricacies of its art, one cannot overlook the year 1950, when Tibet was annexed by China. This period serves not merely as a historical backdrop but as a critical turning point in the tapestry of Tibetan identity and spirituality. It unfolds layers of resilience, especially when we glance at the detailed, symbolic world of thangka art.

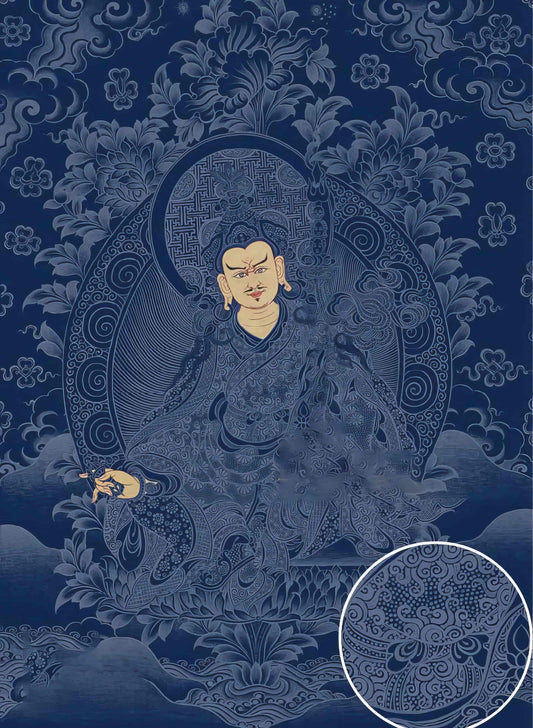

Thangkas are more than just paintings; they are spiritual guides that embody devotion and discipline. Intricately woven with Buddhist iconography, these scrolls are painted by trained artisans who spend years perfecting their craft. Each brushstroke in a thangka tells a story, echoes a prayer, or represents a spiritual lineage. During the tumultuous times post-1950, thangka artists faced the challenge of preserving their sacred art in the face of cultural disruption.

Natural pigments, derived from minerals like lapis lazuli or gold dust, whisper tales of endurance against time. These traditional materials became even more significant as the preservation of authentic techniques became a form of resistance. In the face of standardization pressures from outside influences, the uncompromising fidelity to these methods became a symbol of cultural survival. I remember a conversation with a thangka artist who spent months grinding and preparing these pigments with meticulous care, acknowledging how each hue must resonate with divine frequencies. It’s a commitment, a prayer in itself.

The annexation also led to a diaspora, scattering Tibetan communities across the globe. With them traveled the art of thangka, adapting yet holding on to its core practices. This scattering was not merely a loss—almost paradoxically—it enriched the canvas. New influences mingled with the old, allowing for a subtle evolution in styles while remaining true to the sacred teachings and iconography. This blend of tradition and adaptability is what keeps the art form vibrant and alive. The thangka's borders may frame static images, yet its heart pulses with the breath of living tradition.

What strikes me most is how Tibetans have guarded their intangible heritage with a fierce yet quiet diligence. Stories of monks and laypeople alike carrying rolled-up thangkas over mountains during their escape remind us that cultures are not conquered as long as they are remembered. For the Western collector or the spiritual seeker who encounters a thangka today, it is not merely an art piece — it is a testament to resilience, a bridge between worlds, and a glimpse into a realm where time is both paused and eternal.

So, when you unfurl a thangka, take a moment to ponder the journey it represents. Consider the hands that created it, the whispers of history it carries, and the sacred teachings encapsulated within each delicate line and color. In doing so, you participate in a continuity that defies borders, a cultural endurance as intricate and profound as the artwork itself.