Tibetan Buddhist Deities Guardians of Spirit and Art

Tibetan Buddhist Deities Guardians of Spirit and Art

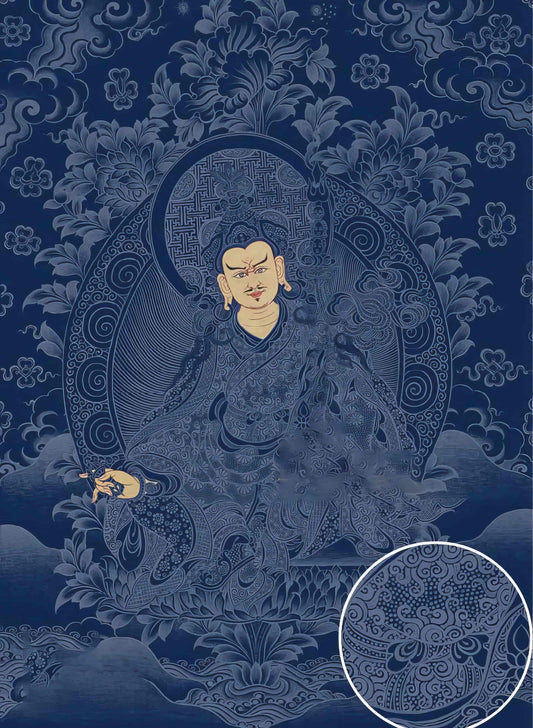

In the intricate art of Tibetan thangka, nothing is casual or without purpose. These vibrant scroll paintings, with their kaleidoscope of colors and complex imagery, serve as visual scriptures and meditative tools. When one gazes deeply into a thangka, the depicted deities emerge not merely as figures of devotion but as profound manifestations of inner truths and cosmic principles.

Take, for example, Avalokiteśvara — the Bodhisattva of Compassion. In many thangkas, you will find him adorned with multiple arms, each hand holding a unique implement that symbolizes an essential aspect of compassion in action. This physical multiplicity is not just artistic license; it is a visual articulation of a boundless capacity to assist beings across the universe. The exactitude with which Avalokiteśvara and his accouterments are rendered is testament to the painter's spiritual discipline, a commitment that transcends mere craftsmanship.

The creation of a thangka is no simple artistic endeavor. Artisans undergo years of rigorous training in monasteries, honing their skills not only in painting but in understanding the sacred texts and spiritual teachings that inform every stroke. Each thangka is fashioned using natural pigments made from crushed minerals and plants, a painstaking process that ensures the colors remain as vibrant and as enduring as the teachings they depict. As your eyes move across the canvas, you are drawn into a world where every hue holds significance — the serene blue of a sky on a thangka’s background might incline you to reflect on the vast, compassionate nature of space itself.

Thangkas also tell the tale of fierce protectors, like Vajrapani, whose thundering presence guards the dharma. Often depicted in a whirlwind of fiery intensity, Vajrapani's role is both protector and destroyer of delusion. While his fearsome appearance might unsettle onlookers, it is potently symbolic of the inner strength needed to break through ignorance. His depictions serve as one of the more immediate confrontations with the divine, one that challenges practitioners to examine the potency of their own resolve.

The evolution of deity representations in Tibetan thangkas also reflects historical and regional variations. As Buddhism traveled along the Silk Road and rooted itself in the Himalayan highlands, these artistic expressions absorbed local influences, becoming a rich tapestry of cultural syncretism. This blending of styles not only enriched the visual lexicon of thangka but also made these deific images more relatable and accessible to the diverse communities that adopted them.

Reflecting on these thangkas, one appreciates not only the artistic mastery involved but also the deep spiritual and cultural narratives they carry. They invite us to engage, consider, and even question the very nature of divinity and compassion. In a world that often moves too quickly to pause, these deities invite us to sit — just a little while longer — in their presence, to reflect on the depth of human experience they so beautifully encapsulate. It’s this kind of quiet, sometimes unsettling, reflection that makes the study of Tibetan deities in thangka art an endlessly rewarding pursuit.