The Art of Thangka: Origins, Traditions, and Aesthetic Legacy

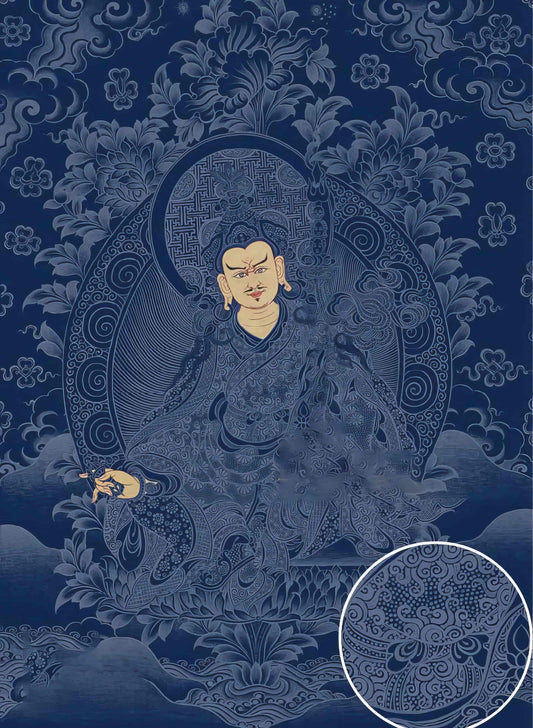

A "thangka" (also spelled "tang ka") is a form of traditional Tibetan scroll painting. Typically created on cloth or paper, thangkas are mounted on silk brocade and hung for veneration in homes, temples, or monasteries. They depict a wide range of subjects—ranging from Buddhist deities and religious scenes to historical figures and symbolic cosmologies—offering a window into Tibetan history, culture, politics, and spiritual life. Traditionally, once completed, a thangka is blessed by a senior lama or spiritual master, often with a red cinnabar handprint or seal on the back. It may also be consecrated by inscribing sacred mantras or placing images of stupas and written praises on its reverse side.

Origins of Thangka

Scholars generally trace the origin of thangka painting to three main theories:

1. The Indian Origin Theory ("Southern Origin")

Some scholars, especially from India and the West, argue that the thangka evolved from Indian cloth paintings known as pata. Scholar Ducci, for instance, draws a linguistic parallel between the Tibetan term tang kha (originally written as ras-bris, or "cloth painting") and the Sanskrit word pata, which also refers to cloth-based religious art. The theory is supported by Buddhist scriptures like The Root Ritual Manual of Mañjuśrī, which uses ras-bris to translate pata. Furthermore, Chinese art historian Huang Chunhe links thangkas to Indian Buddhist cloth art that flourished between the 7th and 8th centuries, asserting that the Tibetan thangka is a local development of this earlier Indian tradition.

2. The Chinese Origin Theory ("Eastern Origin")

Other researchers propose that the word "thangka" is a transliteration of Chinese, and that its scroll format evolved from Tang Dynasty hanging scrolls. Professor Xie Jisheng suggests that thangka painting may derive from early Chinese banner paintings, such as the T-shaped silk banners discovered in the Han tombs at Mawangdui. These banners, which symbolized the soul’s ascension to heaven, bear striking compositional similarities to thangkas, including the placement of sun and moon motifs. The central decorative brocade strip in a thangka, called the "door ornament" in Tibetan, is thought to derive from these early Chinese prototypes.

3. The Indigenous Tibetan Theory ("Local Origin")

A third theory holds that thangka painting is an indigenous Tibetan art form with roots in the ancient Bon religion, which emphasized elaborate rituals and the veneration of cosmic deities. In this context, the Tibetan word tang originally referred to animal hides—especially deerskin—which were used as painting surfaces. Over time, these evolved into more refined cloth-based paintings. As Buddhism took root in Tibet, Indian masters like Padmasambhava incorporated local customs and visual symbols to facilitate the spread of the new faith.

Categories of Thangka

Thangkas come in a variety of forms based on their technique and materials:

Embroidered Thangka – Created by stitching colored silk threads into detailed compositions. Known for durability and refined craftsmanship.

Kesi (Cut-Silk) Thangka – A complex silk-weaving method using discontinuous weft techniques. Produces a three-dimensional effect with vivid texture and elegance.

Brocade Weaving (Zijin) Thangka – Woven from satin or brocade, combining colored threads to form intricate religious motifs.

Appliqué Thangka (Tapestry) – Composed of colored silk shapes (figures, animals, architecture, etc.) cut and stitched onto a base fabric. The appliqué thangkas from Kumbum Monastery are especially renowned.

Painted Thangka – The most common type, painted on canvas, animal hide, or paper. Traditional pigments include ground minerals and precious metals. Some later works were woodblock-printed, known as “printed thangkas.”

Pearl Thangka – A rare, luxurious form where thousands of pearls or gemstones are sewn into the image. The Tara thangka at Chamchoe Monastery is a famous example.

The History and Evolution of Thangka Painting

Tibetan painting developed under the influence of Nepalese and Chinese art. This cross-cultural fusion began as early as the 7th century during the reign of Songtsen Gampo, who married Nepalese princess Bhrikuti and Chinese princess Wencheng. Both brought artists and artisans into Tibet, giving rise to what became the “Nepalese school” and the “Han-style influence” in Tibetan religious art.

From the 10th to 12th centuries, Tibet was fragmented politically but flourished artistically. This period saw the rise of two major regional styles:

U-Tsang Style (Central Tibet) – Influenced by Indian Buddhist art, particularly Pala-style imagery. Subjects were mostly deities, with a central figure occupying the main visual space and surrounding smaller attendants.

Western Tibetan Style (Ngari region) – Shaped by artistic exchanges with nearby Kashmir. Paintings from this area had a more worldly, secular quality. Figures were stylized, with round faces and spontaneous gestures. The layering technique and early use of perspective added visual depth to the compositions.

By the 13th and 14th centuries, monastic expansion created greater demand for religious imagery. While Nepalese techniques continued to influence artists, homegrown Tibetan painters began asserting their own aesthetics. One such figure was Jiwugampa from Yarlung Valley, whose work introduced indigenous themes and Tibetan sensibilities into sacred art.

In the 15th century, the Mentang School emerged under the painter Mentang Döndup Gyatso. This school emphasized strict iconometric rules (from Indian treatises like the Measure of Sacred Images) and a distinctive blue-green palette. Mentang painters pioneered the use of natural Tibetan landscapes—glaciers, rivers, rocks—as backdrops. They also incorporated Chinese elements such as floral motifs and bird-and-flower paintings.

A parallel school known as the Qinze School, founded by Chinze Chinmo, favored bold contrast, flat color blocks, and robust masculine deities with dramatic expressions. While Mentang leaned toward elegance and spiritual harmony, Qinze embodied strength and visual intensity.

In the 16th century, Garma Gazi School was founded by Nangka Zashi, blending the techniques of Mentang and Chinese gongbi (fine-line) painting. Gazi painters excelled in rendering nature: waterfalls, mist, and foliage became signature motifs, creating poetic, dreamlike landscapes.

By the 17th century, painter Chöying Gyatso combined Gazi with Qinze and Mentang elements to form the New Mentang School, which soon spread widely across central and western Tibet.

In the 18th century, Dege’s master Pubu Zeren, praised as a reincarnation of Vishvakarman, became influential in eastern Tibet. He introduced asymmetrical compositions and refined brushwork. His works used visual space skillfully, combining density and emptiness in harmonious tension.

How Thangkas Are Made

The making of a thangka is a complex and devotional process:

Surface Preparation – A piece of cotton is stretched over a wooden frame and coated with a mixture of glue and chalk or clay, then polished with a smooth stone until it’s like ivory.

Sketching – Outlines are drawn with charcoal sticks or ink based on strict iconometric guidelines. Each deity or figure must conform to precise spiritual proportions.

Color Application – Natural pigments such as ground turquoise, coral, and malachite are applied. High-end thangkas use gold powder for highlights and halos.

Mounting – The finished painting is lined with silk brocade and attached to rods at the top and bottom. A yellow veil is often added.

Consecration – The thangka is blessed by a lama, who writes sacred syllables (e.g., "Om," "Ah," "Hum") on the reverse and conducts rituals to "bring the spirit" into the painting.

How to Authenticate a Thangka

Collectors and practitioners look at several indicators to determine authenticity:

Date and Style – Pre-19th-century thangkas use natural mineral pigments and simpler, earthier palettes. Newer ones often show softer tones and detailed shading influenced by Chinese styles.

Provenance – Works from monasteries or noble households often use real silk, gemstones, and silver accessories. Temple-origin thangkas may carry seals or blessing marks.

Wear and Patina – Older thangkas have natural signs of aging: incense stains, cracks, and soft faded tones. Fakes may show unnatural distressing techniques like chemical burns or hand-rubbed soot.

Materials and Technique – Quality of silk, brocade, pigment absorption, line precision, and iconographic accuracy all impact value.

Subject Matter – The presence of rare deities or refined compositions adds value, particularly if painted by known lineages or schools.