Shiva in Tibetan Buddhism

Shiva in Tibetan Buddhism

The majestic tapestry of Tibetan Buddhism weaves together threads from various spiritual traditions. Among its rich array of deities and symbols, one might be surprised to find a figure central to Hindu tradition—Shiva. This inclusion might seem unexpected, yet it unfurls fascinating insights into the syncretic nature of Tibetan spiritual art and belief.

In Tibetan Buddhism, Shiva is often revered as Mahākāla, a fierce protector deity who aids practitioners by dispelling obstacles on their spiritual path. While Mahākāla's roots are intertwined with the Hindu Shiva, his role and iconography have evolved, reflecting the unique contours of Tibetan Buddhism. This transformation can be traced back to the transmission of Indian Buddhism into Tibetan lands, where Mahākāla's fierce energy became aligned with the fierce compassion and wrathful protection valued in Vajrayana Buddhism.

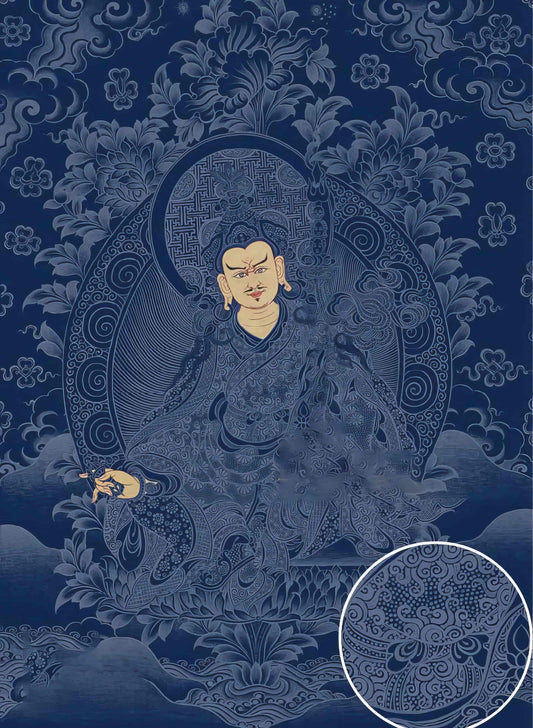

When depicted in thangka paintings, Mahākāla is often shown in a fearsome form, his face a mask of wrathful determination, engulfed in flames of wisdom. These thangkas are both a testament to the intricate skills of Tibetan artists and a vibrant expression of devotion. Each brushstroke and color is imbued with meaning; for instance, the dark blue or black hue of Mahākāla's body symbolizes the transcendence of ignorance and the embracing of emptiness—key tenets of Buddhist philosophy.

What fascinates me personally is the rigor and dedication required in crafting these thangkas. Artists undergo years of training, mastering the meticulous lines and fine details that bring deities like Mahākāla to life. They use natural pigments derived from minerals and plants, ensuring that each hue has its own life and energy. This process is not just artistic; it is deeply spiritual. The creation of a thangka is as much a meditation and act of devotion as any other practice in Tibetan Buddhism.

Beyond the painting process, there lie deeper questions about the cultural dialogues that allow such syncretism. How did Shiva from the Hindu pantheon become Mahākāla in the Vajrayana tradition? This intersection speaks to the fluidity and openness in spiritual exchanges along the ancient Silk Road, where ideas and beliefs flowed as freely as the goods that fueled those ancient trade routes. Tibetan Buddhism, in its essence, is not a closed system but one that has embraced diverse influences to cultivate a rich tapestry of wisdom and practice.

For those who stumble upon these depictions of Mahākāla in Tibetan monasteries or art collections, the encounter can be a powerful one. It’s a reminder of the fluid borders of art and spirituality, where one tradition’s deity can become another's protector. In the end, these cross-cultural dialogues highlight not just differences but shared journeys in the pursuit of transcendence and understanding.

And maybe, standing before a thangka of Mahākāla, that shared journey is something we can all feel a part of—a testament to humanity's ever-curious spirit and our shared endeavor to connect with the divine.