How to Draw a Thangka

How to Draw a Thangka

Imagine a long journey that begins with a single dot on a canvas, a grain of golden sand on a vast beach. Drawing a thangka is akin to entering a world where every line is a thread in a rich tapestry of spiritual symbolism. Even as I describe it, I can’t help but feel a shiver of reverence for this art form, steeped in tradition and deep meaning.

A real thangka is not a weekend project; it is a commitment. It begins with the careful preparation of the canvas, typically a cotton or silk cloth stretched on a wooden frame. The surface is then treated with a mixture of white clay and animal glue, creating a suitable base for the colors and details that will come. This is more than just pragmatism; it’s a cleansing ritual, an act of devotion that sets the tone for the spiritual journey ahead.

The Tibetan art of thangka painting is profoundly symbolic—every curve, dot, and color carries a specific meaning, and learning this symbolic language is crucial. For instance, the lotus often graces these canvases, symbolizing purity and enlightenment, blossoming unstained from the mud. Drawing a lotus is not merely about aesthetics; it's an exercise in meditation, contemplating the unfolding journey toward enlightenment.

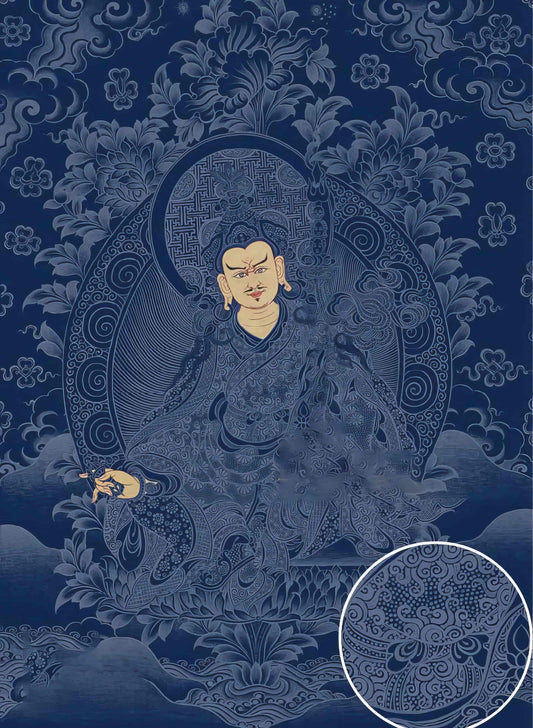

Natural pigments mixed with a binder like yak glue are used to achieve the vivid colors characteristic of thangkas, each imbued with its own symbolic significance. The deep blues and brilliant reds are not chosen at random. Blue, often a symbol of compassion and healing, paints the robes of deities like Medicine Buddha. Red speaks of power and passion, a divine energy that can both create and destroy.

A storyteller at heart, I always find myself marveling at how these pigments are ground from minerals—lapis lazuli, malachite—and transformed through ritual into something sacred. The act of sourcing these colors historically was an immense endeavor, crossing mountains and rivers, a pursuit of beauty that mirrored the spiritual quests of the monks who commissioned the paintings.

As you sketch the deities and mandalas, remember that symmetry is key. This is not just a guideline; for Tibetan artists, it is a reflection of cosmological balance. The use of a grid ensures this harmony and precision. Each deity’s face, according to tradition, should be sketched under the guidance of a master. Indeed, much of the training involves mastering these canons of proportion. It's humbling to think that one could spend years—or even decades—in apprenticeship, learning to draw a single deity’s eyes.

Crafted for meditation practice, thangkas are not merely objects of art. They are spiritual tools, representations of the divine, and windows to the inner workings of the mind. When finished and consecrated, the thangka becomes a living presence, something both exquisite and profoundly sacred.

Engaging with thangka art is not so much about drawing perfect lines as it is about drawing from a deep well of intention and patience. It’s pulling inklings of the divine into the realm of the visible. And perhaps, as you slowly bring a thangka into being, you’ll find that you’ve also drawn something else's—a map of the heart, charted, line by delicate line, in devotion.