Amid the Colors Tibetan Art and Identity Under Chinese Occupation

Amid the Colors Tibetan Art and Identity Under Chinese Occupation

When Tibet fell under Chinese control in 1950, a whirlwind of political and cultural change swept over the land. For those who paint and preserve thangka, the traditional Tibetan scroll paintings, this shift became more than just a geopolitical crisis. It marked a time of significant transformation in how Tibetan artists practiced their craft and preserved their spiritual heritage. As a lover of thangkas, I find their resilience during this period both striking and inspiring.

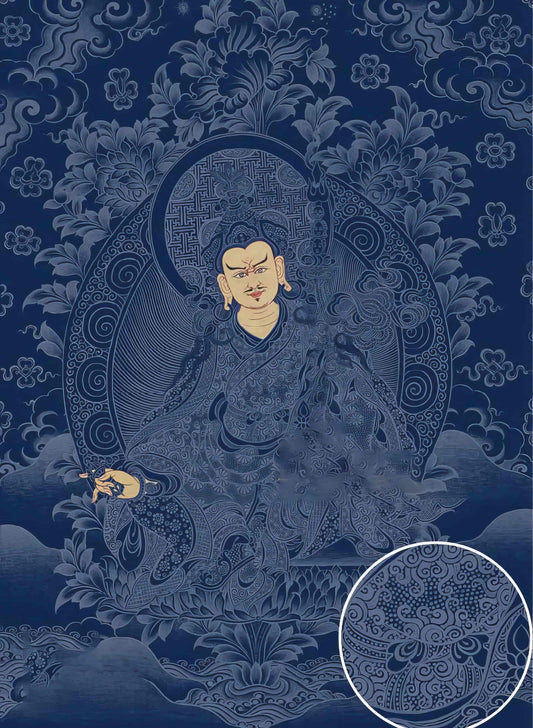

Imagine a thangka artist at work, hunched over a canvas with delicate brushes and a palette of colors derived from mineral and botanical sources. Each pigment—lapis lazuli for majestic blues, gold dust for divine halos—carries with it centuries of tradition and symbolism. But during the Cultural Revolution, access to these natural materials was disrupted. Many sacred rituals, which were integral to the creation process, had to adapt silently or risk being lost. In the absence of traditional pigments, some artists turned to synthetic substitutes, yet they retained the meticulous brushwork and iconographic details that are the heart and soul of thangka painting.

While the tools changed, the essence of thangka remained intact. The pigments might have differed, but the artist's intent—to create a bridge between the earthly realm and the divine—never wavered. These paintings became quiet acts of resistance, each completed thangka a testament to the artist's determination to preserve Tibetan identity and spiritual lineage.

Then there’s the spiritual lineage, a thread woven through Tibetan culture and particularly central to thangka making. Historically, students would endure years of apprenticeship under a master, learning not just the technical skills, but also the rituals and spiritual discipline required to create thangkas. Such training persisted even amid the tension and restrictions of occupation. Masters risked everything to pass on their knowledge, often moving in secrecy, carrying their lessons like whispers through the mountains.

In this climate, the role of the thangka evolved. It became a portable repository of culture, a vivid reminder of a homeland facing profound change. Those outside Tibet who came to possess thangkas during the diaspora found themselves not just collectors, but custodians of a rich tradition.

Today, when I observe a thangka, I see more than exquisite detail and vibrant colors. I see endurance and transformation. Thangka artists, past and present, have remained faithful to their cultural heritage under immense pressure. These paintings remind us all of the resilience of the human spirit and the profound role art plays in preserving identity. And maybe that’s what I find so compelling: these pieces are not merely beautiful objects; they are stories of survival, adaptation, and devotion in a world that never stands still.